A complex understanding of faith was modeled for me at a young age, and I imitated that model for most of my life. The model for me was an encounter when I was very young, maybe as old as ten, with an elder Anglican priest. I was confused about all the conflict over evolution. I understood the science (as well as anyone at that age can) and didn’t know what to think about the religious side of the question. So I asked this trusted cleric. He smiled and told me calmly that there is no conflict between science and religion. God made the world, and science helps us understand God’s world better, he said.

Allowing for this kind of complexity of faith allowed me to explore faith outside my own culture, and learn about Buddhism, Hindism, and as I grew older, I learned that there were religions specific to indigenous peoples around the globe that were still being practiced. Cultural detritus from a popular craze in spiritism in the late 60s gave me access to methods of divination and an interest in meditation and astral travel. The world of faith seemed vast, but the one that seemed to make the most sense to me from the start was Buddhism.

My first encounter with Buddhism came prior to my realization that paganism was possible. I read the Zen classics by Suzuki and Watts, and bent my pre-teen mind around the sound of one hand clapping. I earnestly attempted meditation while I contemplated tasty berries and missing fingers. I can’t say that I understood everything all at once, but the continued exposure over time left a mark.

Buddhism was for me, first, an escape from Christianity. It was a release from the limitations of that two-dimensional theology and its utterly inexplicable expectations on men and women. The effort needed to strive toward enlightenment was understandable, it seemed achievable. Pleasing the fickle and contentious god of the Christian Bible seemed impossible. Buddhism freed me from the authority of the Church, and Christian moralists — their opinions were suddenly irrelevant.

I was exposed to Greek myths very early in life, and read or watched the stories about the Greek gods several times before college without ever once thinking about the people that used to worship those gods. The myths were presented as funny stories from primitive, deluded simpletons, and not as elements of sacred and holy worship from our ancestors. My experience with religion up to that time was mostly Anglican, with a smattering of other Protestant and Catholic services (often funerals) thrown in.

I couldn’t help but notice, though, that the Greek gods were a lot more life affirming and fun than the “father, son, and holy ghost” guilt train. It made me wonder, more than once, how Christianity ever got a foothold over those other faiths. Although, stories of modern evangelical colonialists imposing their faith at the end of a rifle gave me some idea about how it could have happened. The persecution stories of early Christians left me mystified: I was a life-long Christian and couldn’t tell you what it was about the faith that was worth submitting to torture and death rather than walking away from. These stories continued to make the least amount of sense, of anything in the whole mythology.

In college, I fell in with an unruly gang of musicians, English majors and anthropology students who scoffed at the dominant culture and embraced the older gods with an egalitarian and enthusiastic spirit. We met weekly on campus and shared with each other everything we had learned. Wiccan initiations, Druidic forest rites, Voudon celebrations of the dead; divination with tarot cards, random books, and dreams. So much cheap incense! So much bad poetry!

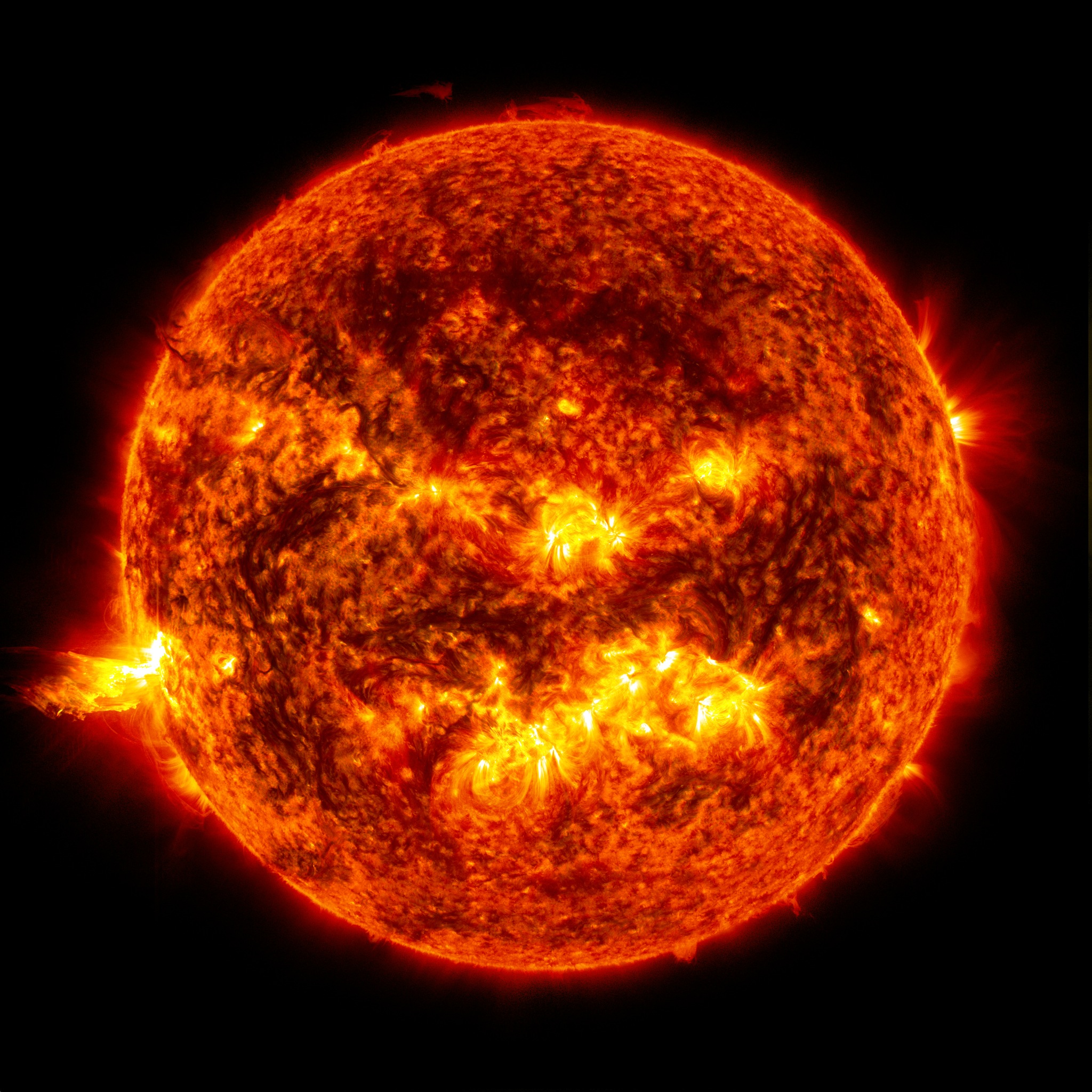

The shared world-view that brought our group together is the one consistent element I’ve seen in nearly every pagan context. At the first is a recognition that the Church does not represent all religion, and is actually wrong about everything. Most pagans accept that everything in the world is sacred, that deity is in everything and everything is of deity, and the most important deities are the ones you actually encounter every day. The sun, the moon, the city; the river, the road, and internet; Justice, Liberty, Victory. And the importance of family, ancestors, and heroes. In most pagan communities, diversity is cherished, and the community that you worship with can become a true family.

We traveled as a tribe to larger pagan gatherings with bonfires and huge group devotional rituals where many of our group found teachers, resources, and friends that launched us into lifetimes of living openly pagan. Whatever that meant. For me that meant having the privilege to perform any kind of rite or worship any sort of deity I chose, along with publicly wearing pagan jewelry and answering questions that inevitably came from them. It meant filling in ‘pagan’ for religion on job applications and jury duty forms, and representing paganism to family and friends. I had the privilege to find it amusing to suddenly find myself a minority.

Since I began my path as a pagan in an informal collective, I had a hard time settling into established groups. (Not for lack of trying.) I don’t like my choices to be limited and I don’t need a priest of any gender to intercede for me with my gods. As I result I disincluded myself from a lot of established pagan identities. I never got on the Wicca train, didn’t do Druidism or tribalism or Norse paths. When people ask, I say I’m pagan, and I don’t usually try to elaborate, regardless of the fact that it’s not really that descriptive of a word.

The term “paganism” is rife with ambiguity. Perspective, personal experiences, and the relationships that are built often color what people understand to be paganism. Some make a distinction between neo-paganism and the native faiths still practiced where indigeneous people live. Some subdivide paganism into groups based on location and academic rigor, considering only some of them to be “pagan”. Others would use a broader brush, and declare anything not Christian is pagan — which might seem shocking until one considers the context is from within a Christian-dominant culture which considers all other faiths to be pagan. But does it make sense to use a Christian framework to define paganism?

With the exceptions of the self-organized rituals and activities our college group came up with on our own, and the spontaneous devotionals I would occasionally present, I found the actual practice of paganism in the real world to be somewhat limited. I wanted to greet the sun and the rivers and the mountains. I wanted to sing with the birds and moan with the goats and bellow with the dolphin. I wanted the stories I celebrated to have meaning in the world I lived in.

Instead, what I got was a dozen variations on Gnostic Christianity, only with more statues! More candles! More dancing! Disco lasers! Enough frankencense to stun a bishop! So! Much! Goth! But also a lot of gatekeeping, authoritarianism, and creepy behavior. To be fair, modern paganism as I have experienced it is very recent derivative of a predominantly Christian culture, and we only had a few templates to work from. Most of us had a Christian upbringing, and after that, it is hard to know how to walk away from it. My practice of faith has been a constant work in progress, rebuilt on the regular with the lessons I have learned.

I blame my willing acceptance of the ambiguity of paganism on Zen Buddhism. One of the best features of paganism that I saw was the near absolute acceptance of diversity and view that all is sacred, thus almost any combination of beliefs that one might want to hold were all considered reasonable — each within their own context. This held hands with my Buddhist beliefs that everything is connected and any believer should be respected just for being another human being on the path. And if you wanted a Buddha and a jackal flanking an Orisha on your altar, that was totally up to you to fly that freak flag proudly.

For a long time, I have considered Buddhism to be a school that trains the mind in a way that maximized clarity of thought and efficiency in action. Paganism is the lens I see the world through, Buddhism is how I deal with what I see. When I went to take action, that would include a prayer to the gods clearly stating my goal. Then it was one step after another to get the job done, dispassionately being there to take the path where-ever it went. Thanks to an early understanding of the complexities of faith, I’ve never seen any conflict in this.

Paganism gives us access to Deities, Heroes, Ancestors, and non-obvious world-views — these are all important and worthy of devotion because they are how we interact with transcendental energies and powers needed to counter the chaos and dynamic of life. Many cultures recognize the helpful gods and the caring ancestors: negotiation with them can lead to many benefits in life. I don’t think there’s any danger in denying the existence of gods, but I don’t also see any significant benefit to walking away from them. Even an atheist can appreciate the utility of focusing the mind and soothing the emotions through regular practice of prayer and meditation in order to accomplish a task. The use of deities just makes it easier.

There exists an understanding of Buddhism that precludes the belief in a soul. According to this school, our egos are simply the result of all the connections we’ve made with others, our interactions and the energy that is thereby moved through the universe. Perhaps then, deities and the dead are of no consequence. Those who cleave to this view may find such a universe to be peaceful without all the noise and clutter of religion. Yet I do not observe that their life is any richer, or easier, for the loss. I also do not begrudge them their choice, as inevitably the practice of devotion includes extra work that can easily be avoided.

The story of the Buddha informs me here. The Buddha was earnestly attempting to find enlightenment in self-denial, and then he decided that neither luxury nor torment led to anything good, choosing instead a balanced path. From this, I have learned to build a kind of boundary around religious activity in order to maintain balance: I look to the gods to instruct and guide, not disrupt causality to attend to my juvenile whims. It is a good-faith attempt to align the chaos of the self in a favorable way by putting myself in the best mindset to accomplish my task. Inasmuch as there is a universe outside our skin that we largely can’t perceive, the gods are my control panel interface to the universe I have no understanding of or control over.

Jung’s ideas about a collective consciousness ring very true in this context. Religious and ritual tools can be used to align a single mind or a cadre, they are extremely powerful methods of psychological manipulation, as they have been developed over tens of thousands of years. Humans appear to have a strong need to connect socially and environmentally: ideas about and rituals concerning divinity and the sacred are universal, and we tend to create familial relationships with our environment (eg: Father Sun, Mother Earth). As ritual taps into the collective unconscious, it makes a connection to divinity shared by many.

To the degree that we are animals that require training and a consistent environment to work at our peak, Buddhism and paganism work in tandem. Just as yoga and exercise build strong and flexible bodies, meditation and right thinking develops robust and flexible minds. Working with the gods provides a mental leveraging force that helps us to focus our efforts and retain physical endurance through difficult conditions. There is a therapeutic benefit to being able to give your tears and your fears to your gods that allows you to meditate more peacefully, train more vigorously, and study more deeply.

The ritual tools of neo-pagan and indigenous cultures invite a connection to the collective focus of divinity that can grant us access to realization and understanding and visions of a better future. The perspective and practice of Buddhism grants us a clear view of the present and an understanding of our fundamental interconnection with the universe. I accept this complexity of faith and allow it to inform and encourage me.

Leave a Reply