The most difficult question I face is one both existential and disparaging: What is paganism?

There is an 1820’s map of the world that divides the continents by religion: Christian, Islamic, or Pagan. Such was the hubris of colonialist imperialism that grouped all the world’s faiths, save two, under the derogatory heading “Pagan”. So broad an umbrella as to be dangerously imprecise, it conflates stone age tribal cults with Persians and Polynesians. “Pagan” expressed an opinion that these faiths were no better than superstition: proof of ignorance and indolence. Consistently on this map, Pagan areas are shown as “barbaric” or “savage” lands, with civilization reserved for Christian or Islamic peoples.

In the first half of the 1800’s, Romantic artists and authors endeavored to capture the wonder and terror of the natural world, and presented localized cultural practices and art as valuable and worthy of preservation. Wordsworth and Coleridge said in poetry what Waterhouse and Friedrich painted in landscapes: scenes of expressive amazement at the power and beauty of the natural world, the wisdom of the farmer, and the genius of local communities. Looking away from mythology or theology to find divinity in the soul of the land and the people that lived on it was the driving force of Romanticism in the early 1800’s and the development of paganism in the 20th century.

In the 1960’s, members of the Spiritism and Theosophy movements popular at the turn of the 20th century attempted to reclaim the word “pagan” to reference modern attempts at pre-Christian faith practice. Ideas lifted from medieval Christian mysticism were built into several competing schools producing systems they called “Wiccan” or “Witchcraft”. The word “witch” was chosen based on old English words used to condemn wealthy, powerful women before having them executed and their property confiscated. These early pagan systems replaced the Christian God with the Goddess and God, or sometimes just the Goddess. These godforms were representative of the Platonic ideal of mother and father. Their world view was rooted in the Theosophic revival of neo-Pythagorean mysticism, highlighting the Platonic elements and the metaphysical implications of numbers.

Today in Europe and America, many modern descendents of Christian culture have tried to revive pre-Christian religions: this movement is generally termed “neo-paganism”. Groups have formed around specific godforms from Greek, Roman, Celtic, and Norse mythologies. Referencing Romantic art and poetry, they build altars, sing songs, and invite their friends to join them in feasts for their gods with bonfires and drums. Summoning Pythagoras, they perform divination and work spells to induce the assistance of their gods. These activities mirror in many ways the indigenous religious activity of Native Americans, Hindu peoples, and Asian Taoist cultures, to name a few, so the question is raised – is indigenous religious activity paganism?

Can we accept newfangled pagan or neo-pagan rites as being as valid as indigenous rites without a heavy dose of colonialism and cultural appropriation? Among the indigenous peoples who had been in contact with Christianity, any reference of their faith practices to “paganism” is still a humiliating denigration. Even if the broad brush of colonial rationalization may conjoin these things, they are products of different processes and cultures. Most indigenous practices stand on their own, while even the most enthusiastic neo-pagan admits that the process of rebuilding the elements of their faith will take many lifetimes of dedication to approach the complexity of most indigenous faiths.

Cultural appropriation is a huge problem in modern Western pagan practice, and it often comes from a desire to achieve a more authentic personal practice. In most cases, a people’s faith is for the people alone, and they simply won’t allow tourists. Taking elements of such a faith as one’s own, calling oneself a follower of a faith from a culture you have no modern or ancestral access to, and worst of all, misleading others about one’s status in a foreign culture, are all painfully common examples of cultural appropriation found in modern pagan and neo-pagan circles, always in people with the very best of intentions. How can validity and authenticity be achieved when all of the source material is off limits?

If you are a white, English-speaking person in the US of A, your options for valid and authentic flavors are thirty thousand brands of vanilla. Roman vanilla. Prussian vanilla. Two kinds of English vanilla. Southern-fried vanilla! Prosperity vanilla! Paranoia vanilla! Space alien vanilla! Vanilla on the TV. Vanilla on the radio. They will all tell you that theirs is the true vanilla, and paganism is anything that isn’t vanilla.

Curiously, it turns out that finding someone who will share your interest in anything that isn’t actually vanilla is a lot harder than you’d think: a couple of millennia of vanilla lovers wiping out everyone else left a mark. Folks who hanker to appreciate boysenberry or rhubarb in the company of others must do their homework and often prove their love of something not vanilla before they can enjoy any flavor besides vanilla in groups.

While the efforts of 60’s era hippies to rehabilitate paganism brought pagan cultures to the mainstream, abuse from domestic terrorists continues to keep the membership of most pagan groups on the down-low. Gatekeeping is a major issue, such that many groups still refuse to practice with other races, other genders, and now transgender folks. It is often the nature of active groups that keeping a low number of members is key to continuity, so even finding an active group with an ‘open seat’ can be challenging, even in a place with many pagan practitioners. And then achieving the seat can be unreasonably difficult, as well, depending on the requirements.

Further, this format of pagan activity has been reducing in popularity. The lifetime of such groups, between personality clashes and time conflicts, is often brief. The chicken-pecking and jockeying for position in hierarchical groups can sour the membership. Occasionally, a bout of toxic egotism or sexual assault between members is enough to put an end to a circle. With the rise of the internet most new pagans follow an independent path, basing their practice on whatever books or videos or movies they encounter. Thus there is an increasing population of isolated, self-identified pagans, who collectively have an extremely fluid notion of what paganism means based on popular fiction and any one of hundreds of instructional books on the topic, and few real-life friends to discuss any of it with.

The word “pagan” is an ugly, awful word, and it describes in the negative a whole universe of beauty and diversity, opinions and variations. It is a misleading word, causing more confusion and tribulation than necessary. It’s a shock word used to freak out staid Protestant parents and authority figures, evoking Satanism and sexual deviancy. Neutral phrases like “Earth-centered”, or “Earth-worship”, or even “Tree worship” are far more direct and appropriate descriptions of what I see normally done under the guise of “paganism”. So why do we even use the word?

One reason is that other words are often worse. Some equivalent words sometimes used in an academic context include “animism” and “shamanism”. While these words have been used to describe the faith practices of specific peoples, their generalized use, especially in the context of a Western neo pagan, is discouraged. The danger of cultural appropriation is high, and the descriptive value is surprisingly low. While a person might describe their work understanding their environment to concoct healing salves as “shamanism”, another might interpret this to mean anything in a range from devil-worshiper to deranged cultist without knowing what a “shaman” even is. For reference, please see that 1820’s map.

The word that we use in our language, in this culture, to describe what we believe is “pagan,” and it’s the one that attracts people who already know that their path is “pagan.” It is, whether we like it or not, our “brand name,” granted to us by our Christian overlords. Since I’m one to make margaritas when given limes, here’s the gift provided by the use of the word “pagan”: anyone claiming to be “pagan” is outside the realm of any Christian authority. Because the Church explicitly defined pagan as outside the aegis of Christianity, pagans retain their own personal spiritual sovereignty – each is their own spiritual boss, subservient to no one. Everything done sincerely with divine intention is valid and authentically sacred. I have the power – and so do you!

Each of us who calls ourselves “pagan” has the power to decide what is important and valuable and how that balance should be managed. With paganism, everyone can define for themselves what is real and what is true based on their own life experience. It allows one to choose for oneself how to see the universe, what gods one will follow, which religious tools one will use. You are the authority for your faith. Your path is valid because you walk it; your faith is authentic because you live it. A religious tradition doesn’t need to be old or famous to be useful, it just needs to be used.

But how does one attain a personal pagan religious practice if all the source material is off limits? A marvelous secret has been hidden, largely in plain sight. Over perhaps hundreds of centuries, humans had devised an entire library of religious tools: processes, ideas, and interactions that allowed humans in groups to weather harsh traumas and retain the memory of cultural and economic activities between generations. Religious tools act directly upon the neurological, subconscious, and semi-autonomous systems in predictable ways to induce a large variety of sensations and behaviors in groups and individuals.

We can see examples of religious tools in use in many cultures, and with careful study, we can start to understand them, abstract them, and apply the mechanics in a local context. Any of these tools, and the multitude of tools that are built upon them, can be used to create a valid, personal religious practice without fear of cultural appropriation. These religious tools are the product of human attention and human understanding, and are the birthright of every human.

In the ancient world, there was a highly diverse and complex network of folks using these religious tools that helped hold together the fabric of the social order for thousands of years. The Roman Empire suffered a dire, self-inflicted catastrophe in which most of these tools were forgotten and the social order collapsed. Some religious tools had been woven into the dominant religious paradigm, such that they were official tools of the faith and continue to be used to this day. It was to our great fortune that other places in the world continued to use the full palette of religious tools, and the advent of anthropology revealed the use of such tools in modern times and well into prehistory. Around the world and throughout history, religious faith in any place has always been a cultural collection of these same religious tools, all used in different ways, for different reasons for each time and place.

Some primary elements of faith – meditation, trance, affirmation, adoration, and initiation – are religious tools found in nearly every faith culture in history. Not every culture used or appreciated every religious tool. The use of music, dance, or representational art are examples of religious tools that are widely used in some traditions, and taboo in others. Paganism allows us the opportunity to explore the use of any and all of these tools in the context of our own lives, our own environments, and in our own communities.

We can recognize the divinity in a tree, a mountain, or a lovely valley. We can name this divinity or not, visit it once or daily. We can chant, sing songs, read poetry, or just stand silently and all are valid forms of adoration. The sacred is all around us, waiting for us to recognize it. To learn about it, and understand it. To dance about it, to perform plays about it. To tell stories about it and include images of it in paintings and murals and giant inflatable parade floats. These religious tools belong to everyone, and pagans are explicitly authorized to use them all.

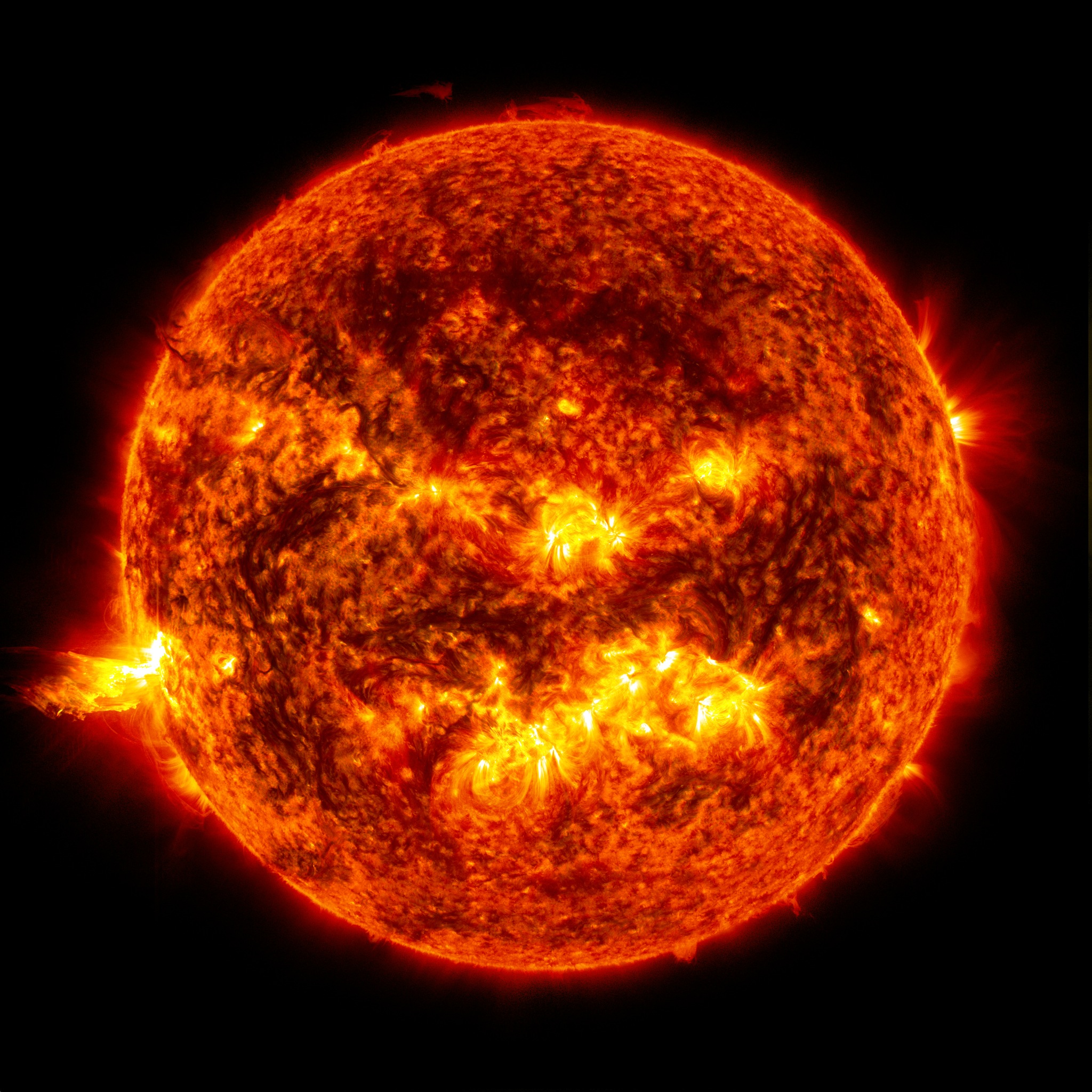

Paganism is the intention to recognize our connection to everything. Paganism is the worship of the whole world through the study of its parts. Paganism is the adoration of all that was and all that is and all that will become. Paganism is the celebration of the mountains and the trees and the critters and the rivers and the oceans and the sun and the sky. We are all part of one organism with many parts, but all one life. When it really comes down to it, what you call this collection of activities turns out to be far less important than doing them.

Your pagan faith practice might not have a name, and might only apply to you. If you haven’t already begun, it could start where you live. You might identify what lives around you – plants, insects, critters, trees. Get to know your neighbors and discover which are your new gardening friends. Plant some flowers and herbs, plant a tree. Take time to recognize the sacred in everything around you. Take regular walks around your neighborhood and get to know the hills and valleys. Say “Hi” to the river as you cross and your neighbors as you pass. Help your friends in need and try to be of service to others. Personal practice is a collection of actions and activities that add benefit to yourself and your community. Make lists of things you would like to do. Keep a calendar and a diary to remember to do everything that is meaningful to you. Your faith practice can and should constantly change.

What is Paganism? It’s whatever we make it to be.

Leave a Reply