Because of my interest in history and in communicating the story of the past to others, I’m always on the lookout for the different ways folks make sense of things. Maps are my go-to: so much makes sense when you can see how nations align geographically, how trade routes and physical obstacles actually guide cultural development. My next favorite and related format is the time chart. Instead of a map with two dimensions of space, it has one of space and one of time, so the changing relationships can be charted.

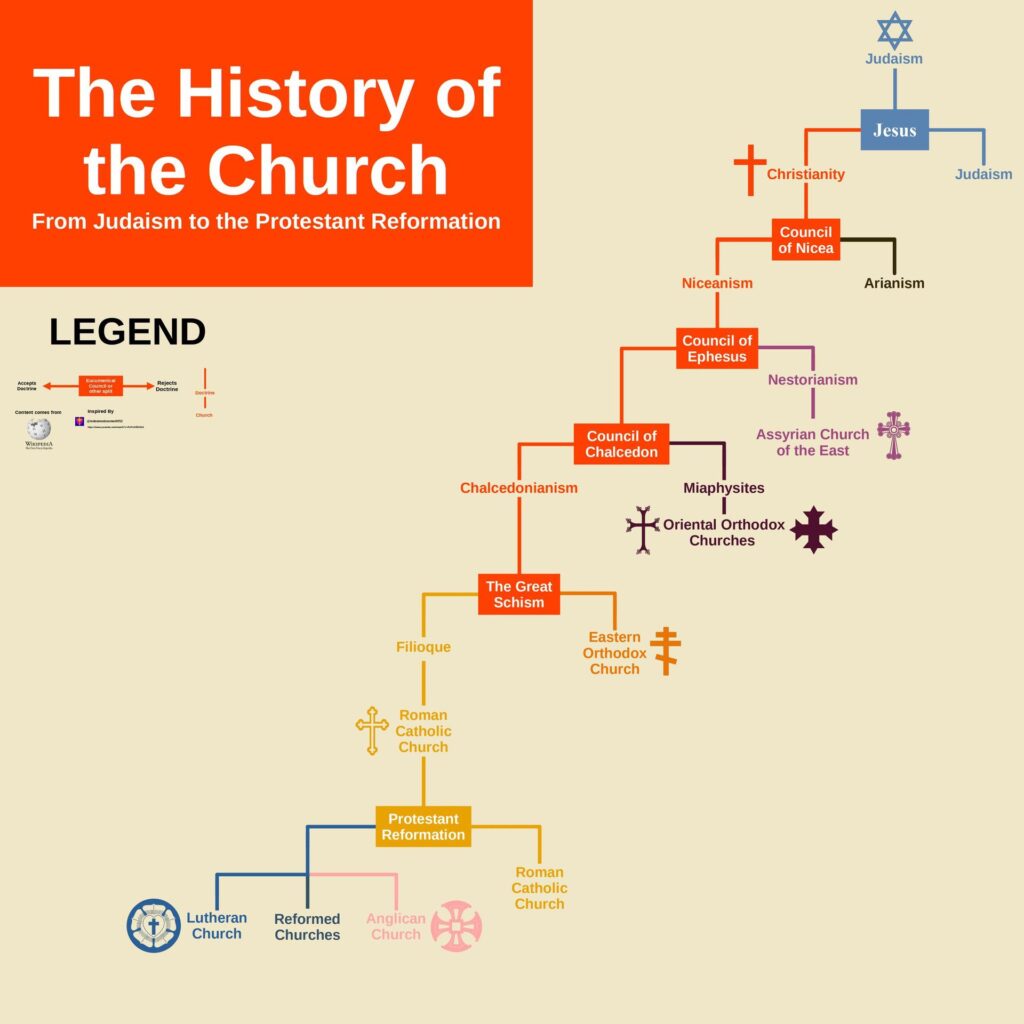

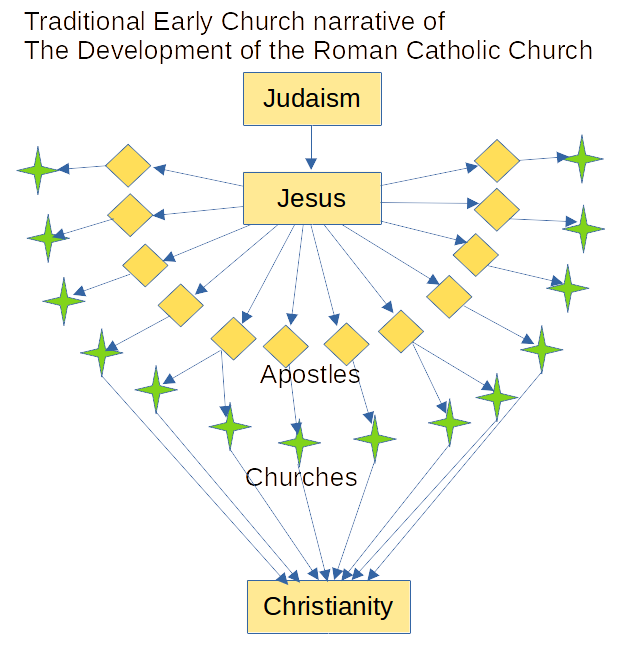

Some folks have made their careers out of creatively displaying information. There is a lot of room for variation, and a lot of information to show. One form of chart attempts to show the development of ideology as a kind of waterfall, from one idea down to another, such as this one titled “The History of the Church from Judaism to the Protestant Reformation.”

I was excited to see such a chart pop up in my social feeds. Not because I think it’s accurate or a good representation of the development of the church, but because it shows what most people today seem to think is the truth. Its simple, naïve perspective on the development of modern theology is so obvious. To be clear, this is intended to be a highly simplified diagram of a pretty narrow window of history, so I’m not going to get bent out of shape arguing that important things may have been left out. There is still a lot here to consider and question.

A Protestant History

The Protestant bias in the structure of the diagram is particularly worth reviewing: it presents a series of doctrinal splits, with the group accepting the doctrine proceeding to the left, while those rejecting the doctrine stalled out to the right. For the Council of Ephesus, for example, the chart shows Nicean Christianity continuing down the left, while the Nestorians rejected the doctrine of Ephesus, and later formed as the Assyrian Church of the East. In a very general sense, the ‘truth’ of this chart shows how modern Protestant churches continue holding the ‘correct’ doctrinal position, rejected by the Catholics, the Monophysites, the Arians, and the Jews.

In a more specific sense, this chart condemns the Jews for rejecting Jesus, and this condemnation is shown through the mechanism of the doctrinal filter: Christians to the left continuing on until eternity, Jews to the right into the chasm of irrelevance. The Protestant bias asserts itself again with the explicit naming of Jesus without mention of Christ. My favorite part is how the Roman Catholic Church seems to appear as an afterthought after the Great Schism, and not, you know, at the very top.

Let’s put some dates on this thing and get a sense for the scale being presented. Judaism reportedly goes back to the 10th century BC, and the range of dates usually given for Jesus is around 5 BC to 33 AD. The First Council of Nicaea was in 325. The First Council of Ephesus was in 431 with the Council of Chalcedon only twenty years later. The ‘Great Schism’ between eastern and western churches occurred in 1054. Martin Luther nailed his ‘Ninety-five Theses’ to the church door in 1517, helping to launch the Protestant Reformation.

In a more specific sense, this chart condemns the Jews for rejecting Jesus.

The Assyrian Church of the East was established in 1553, but there was a ‘Church of the East’ that broke away from the Catholic (‘Western’) church in 410. The Eastern Orthodox churches were separated from Catholic communion in 518, but there were many sub-schisms and rejoinings, so the arrangement between Catholic and Orthodox is very confusing. Lutheranism was condemned by the Pope in 1521, and the Church of England was established in 1534.

Note how the top of the chart starts with Judaism, and after encountering Jesus the Jews then continue on in their ignorance with Judaism. The first mistake here is to confuse the Temple Judaism prior to Jesus with Rabbinic Judaism after the destruction of Jerusalem. It is vital to recognize that the faith of the peoples who lived in the lands between Egypt and Persia along the Jordan River was strongly localized around several politically important temples run by several politically important families. Their primary cultural conflicts rose up around how ‘Greek’ or ‘Persian’ they were. Only after the Romans destroyed those temples and drove those people away did their descendants create the faith-in-exile we call Rabbinic Judaism.

Temple Judaism did not exist as some sort of monolithic entity. It was a highly fractious and divisive society composed of generations of prior ruling families with cultural links to Egypt, Persia, Greece, and Syria. Their (biblical) history of near continuous inter-tribal warfare was only broken by a series of invasions from Syria, and later Persia, who both used a policy of exile to keep rebellious families in line. After the kingdoms left by Alexander faded, this region regained both sovereignty and combativeness, where each king excelled in cruelty, and rebellions boiled in every town. It was this constant warfare that Rome was originally invited to settle in the second century BC.

At the potential danger of complicating this simple diagram, it’s important to point out that modern theologians usually connect Jesus not with the mainstream or dominant schools of Judaism, but to an outcast branch. The implication of this diagram that Jesus came from Judaism, especially when we freely admit he wasn’t representative of the faith of his own time and place, is problematic. But the biggest problem with the assertion that Christianity came from Judaism is that they share nothing culturally. They have different calendars, different holidays, different rituals, different traditions.

The presence of the Jewish holy scriptures in the Christian holy book has long been one source of the misunderstanding that Christianity started as a Judaic offshoot. But Judea wasn’t the origin of Christianity: Rome was. Christianity was specifically forbidden to Jews. They could only be Jewish. Only Romans could be Christians because Christians were the best Romans.

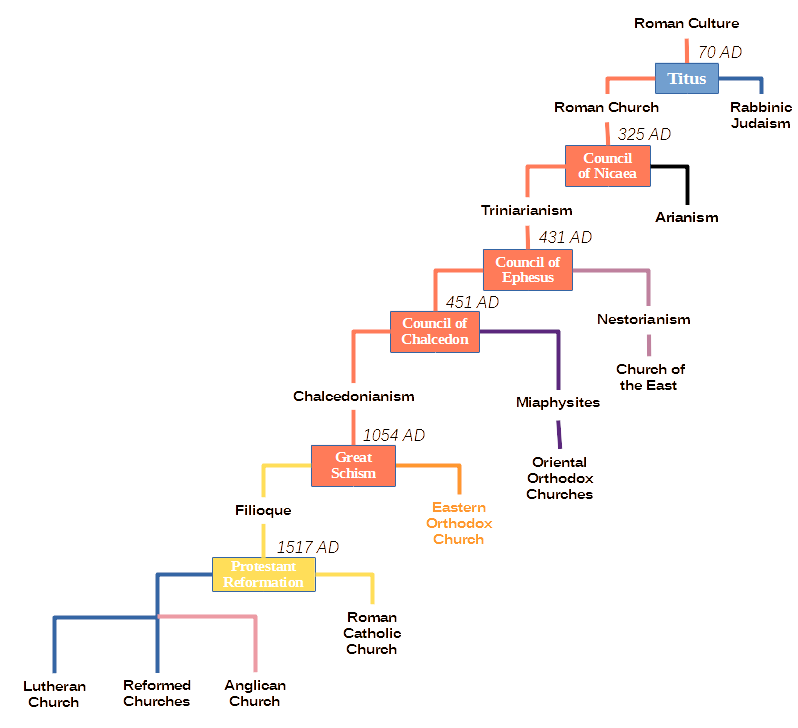

First revision

There is a connection between Christianity and Judaism: it was the Roman destruction of Judea in 70. That’s where Rome intersected Judaism. The Jews didn’t reject Christianity, the Jews rejected Rome. They rejected having a Caesar or Emperor categorically. The Jews violently rejected Roman culture, and so Roman legions rejected the Jews.

The narrative of the Gospels reflect the chaos of the time, with some Jews embracing Roman culture, many others rejecting it, and one man warning that Rome should be accepted and embraced or doom would fall upon them. As these books were written after 70, this wasn’t intended as a prophecy, but as a warning that everyone needed to be “good Romans”. Christianity was born as a celebration of the destruction of Judean culture through the superiority of Roman culture.

It seems to require a branch of Temple Judaism had existed so much like Roman culture that Romans just moved right in.

As such the top icon on this chart should not be ‘Judaism’ but should be ‘Roman culture.’ The destruction of the Temple by the Flavian Caesars would be the sieve that separated the Jews from Roman Church.

The next step in the chart is the Council of Nicea, and while this did serve to separate the Arians from the Trinitarians (here ‘Niceans’), putting this here right after ‘Jesus’ implies that the whole of the development of the Early Church happened without conflict or event as momentous as the ones that are presented in the chart. It seems to require a branch of Temple Judaism had existed so much like Roman culture that Romans just moved right in. This kind of hand waving over the very critical details of the development of the Church is infuriating. Without those details, this range of this chart is not from Judaism to Protestantism, but instead is only the history of the Church from Martin Luther back only as far as Constantine (4th century).

A Catholic History

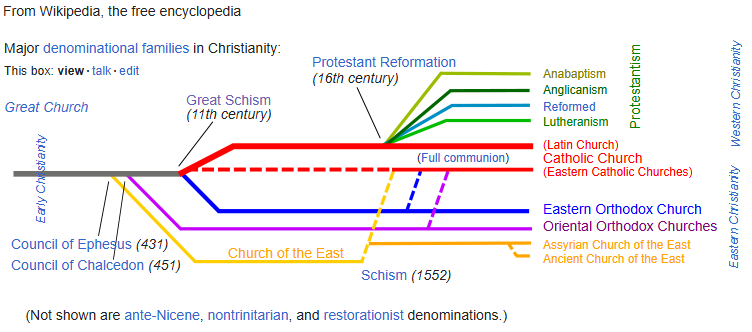

By measure of comparison, this also very simple chart below from Wikipedia shows a more Catholic-biased descent chart, indicating dated events and the ‘branching off’ of different denominations. Note here that the Protestant sects are shown as being further off center than the Catholic ones. Again, this chart waves its hand at ‘Early Christianity’, whatever that was, and doesn’t really start paying attention until the Ecumenical Councils of the 5th century.

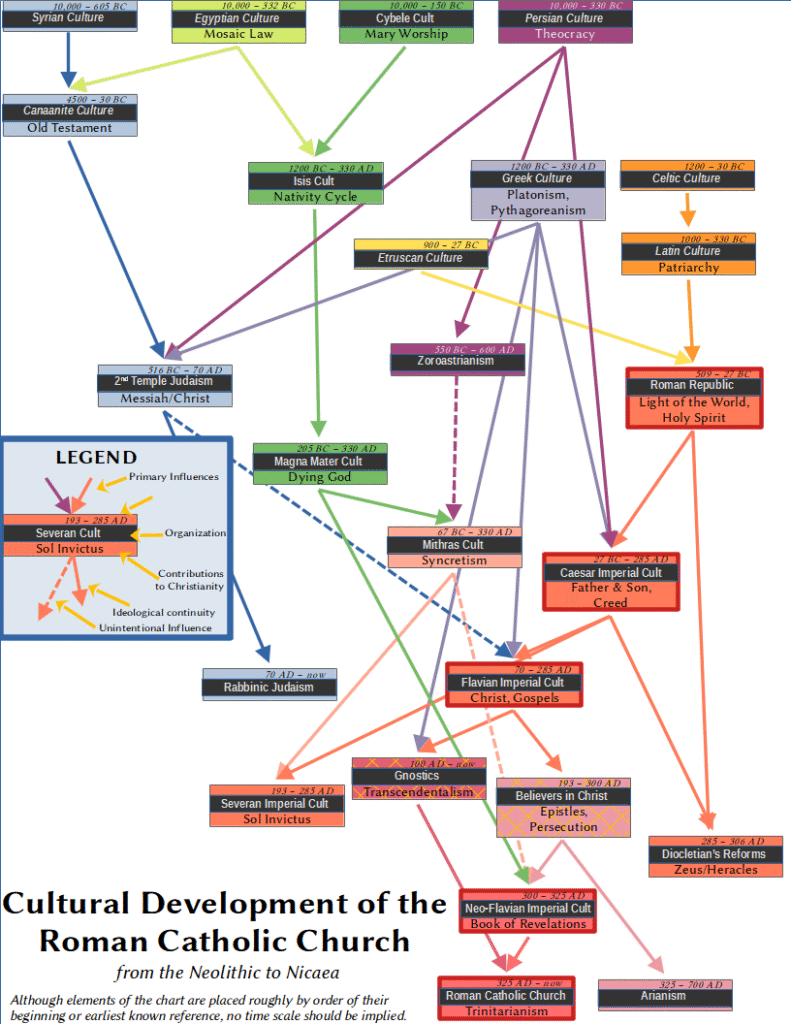

If we could look at a chart that showed what came before the Nicean Council, one might be able to see how Christianity developed. According to many sources, those early years looked something like this:

Here we see how Jesus, a Jew, spread his word to his apostles, who then formed the churches that formed Christianity. No names or dates needed! Certainly no Romans involved! While this chart is laughable, it represents the sum total of what most Christians seem to believe about the Early Church.

What I wanted to see was a chart that showed how the various cultural elements that formed into Christianity developed and wove themselves into the larger culture. I had long harbored the sense that there was a single source of Christianity, but it turns out that this is very far from the case.

Christianity is a syncretic religion, meaning that it contains elements of many different faiths. The Romans did this out of a sense of cultural unitarianism, always seeking ways to weave the elements of the cultures they subjected into the imperial culture. What this means here is that there wasn’t just one ‘source’ of Christianity, but many. I was able to make a chart for it, but it’s not simple.

Christianity is the political merger of the Roman Imperial Cult and the Great Mother Cult.

Cultural Development of the Church

For as crowded as this chart is with boxes and arrows, I’m leaving a lot of important context out. The boxes are roughly arranged in terms of location and time, but there’s no information about ancestral cultures, motivating causes or other related minor cults. Also, several of the boxes are historical references unfamiliar to many people.

The top two rows of boxes roughly corresponds to Neolithic cultures. The third row begins with the Iron Age. The bottom two boxes reference the 4th century, for a rough scale. Each box represents a culture (in italics) or an organization (in plain text). The relevance of each item to Christianity is shown at the bottom. The relationship between the boxes is shown with the lines with arrow heads at the destination. A dashed line indicates the influence was unintentional. Note that lines can cross and flow behind boxes without meaning anything. Organizations primary to the creation of Christianity are shown with the thick red border.

Rabbinic Judaism, for example, is shown here to be a product of Second Temple Judaism, which is shown to be a product of Canaanite, Greek and Persian culture, while Canaanite culture has roots in Egyptian and Syrian culture. The concept of ‘Messiah’ from Temple Judaism contributed to the Flavian Cult’s creation of ‘Christ’ as an object of worship.

If you were to put together a case based on the causal elements of the story, you might say the story is that Christianity is the political merger of the Roman Imperial Cult and the Great Mother Cult. But there was never any intention at any time before the 3rd century for anyone to create Christianity. It’s just what happened over time, organically, within the context of a repressive, brutal culture. Further, there was a lot of mixing between cultures at every step. There wasn’t a single source of Christianity, but many.

The Great Mother Cult started long ago, and has had many names: we’ll start with Cybele. Cybele worship traveled around the Mediterranean and took form in Greek and Egyptian cities as an Isis cult. In Roman areas, it became the Magna Mater cult, but repeated the same mystery school plays, and told similar stories. Magna Mater informed Mithraism, but also the Neo-Flavian cult, where the stories and statues of Isis and Horus are lightly revised for Mary and Jesus. Many of the seasonal and family rites performed by the Church today derived from Great Mother worship activities. For many Christians, especially those who venerate the Mother Mary, the source of much of what they practice comes from the Great Mother cult.

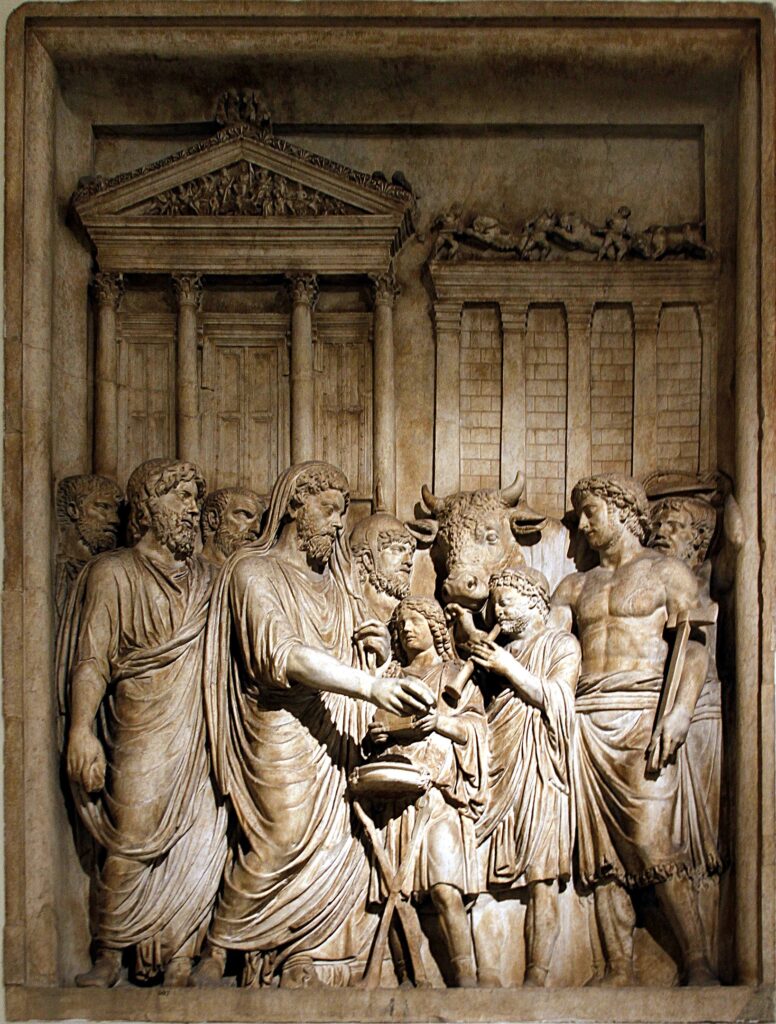

The Imperial Cult was started after Gaius Octavian became Caesar Augustus and the chief priest of all religions in the world. He had the Senate raise his father, Gaius Julius Caesar, to the position of a god in the heavens. Augustus then announced that he was the Son of God and had temples built in all the major cities with great statues and priests to lead good citizens in the worship of Caesar and Augustus while keeping the regular observances of Imperial holy days, like Caesar’s birthday. The cult celebrated Latin culture and the principles of the Roman Republic in the form of the ‘Spirit of Rome’. The elements of the cult were recited, as a creed. Later during periods of conflict between various claimants to the title Caesar, slightly differing creeds were used to recognize supporters for each side.

The Flavian Cult was created because the new family holding the title Caesar didn’t come from the Julio-Claudio line, and the new cult fashioned the rationale for their rule. It celebrated the military victories of Titus in Judea, where he crushed the endlessly violent and rebellious Judeans, and set a new level of authority – Titus was Christ, he had been anointed: a Messiah or Christ is given the right to rule from God. Proof was the fact that they now controlled Jerusalem, or whatever was left of it. A series of Emperors widely considered to be the best were all in the line of the Flavians. The golden age of the empire was reached during the Flavians when the empire attained its maximum size.

When the Severan family took power, they too established a new Imperial Cult, this time exalting Caesar as the Invincible Sun. The Flavian Cult fell out of power but retained a loyal following of ‘Believers in Christ’, who dreamed that a Flavian would come to rule the Empire again. They would hold to this belief even to the point of persecution and write letters to each other to keep their spirits up.

This dream came true when Flavius Constantine usurped control over Empire, by leveraging widespread anger over Diocletian’s Imperial Cult reforms. He brought together the Severan cults and the Magna Mater cultists with the Believers in Christ into a new Flavian Cult that divided the resources of his enemies within the Empire. At his moment of triumph, he solidified the formation of the Roman Catholic Church at the Council of Nicaea where Trinitarianism was established as the critical creedal element.

So there you have the creation of Christianity as a product of Imperial family posturing and nationalist propaganda manifest in the form of a celebration of Roman culture and traditions. And, we’re well positioned at the 4th century to link this chart to the others above, talking about how the Orthodox and Protestant churches originally formed.

Leave a Reply