(back to Imperial Cult)

Nero was a successful emperor, and among the many troubles he addressed, he had decided to deal with a problem long recurring in Judea. After decades of intermittent conflict with local “messiahs” determined to overthrow foreign rule there, Nero had sent four legions of Roman soldiers, led by General Flavius Vespasius, to sweep through the whole of Judea: any towns that didn’t immediately accept Roman rule were looted, burned, and flattened, while its people were starved, crucified, or sold into slavery. Famously, the great temple in Jerusalem was destroyed and the temple mount turned into a garbage dump. (A century later, Hadrian had to go through Judea again with his troops, and it may have been then that the temple mount was turned into a garbage dump.)

While this was all going on, Nero was assassinated, leaving the House of Gaius without an heir. After a year of civil war, the Senate named the top general – Flavius – as the new emperor. He went to Rome to become Caesar Vespasian and his son, Titus, took over as general for the rest of the Judean campaign. The Flavians had the support of the Senate, and so that was enough to get them in the door. But the Flavians weren’t a part of the House of Gaius that had established the imperial franchise. It was clear that the Flavians needed a way to modify the Imperial Cult to make it okay for their family to be the new emperors.

The Flavians created a story about the Judean campaign in the context of a prophecy that included explicitly naming the Flavians as legitimate emperors. Three stories – attributed to Matthew, Mark, and Luke – were told of a Judean whom God in heaven named his son, and who thereafter walked the length of Judea telling others that the Romans were coming to squeegee them into the sea. In the stories, the Jews fail to believe this messenger and seal their own doom. These books were first produced alongside Josephus’ Wars of the Jews, which described the Flavian military adventure in detail so that the connection between the ‘prophecy’ and the Flavians was clear.

This story was accepted gleefully by the up-and-coming families of Empire who built Flavian cult temples in their cities. The Flavian years were relatively successful, although marked with tragedies like Pompeii. Even though the last Flavian, Domitian, was killed by his courtiers after 15 years of leadership, the transition to the Nerva-Antonine dynasty went without issue. This may have been due, in part, by the mythology of the Imperial Cult, which continued to allow ‘God in Heaven’ to choose the next Son of God. The Romans must have felt this was helpful because this began a period of growth that included the “five great emperors”, and the peak of Imperial reach.

The ancient and fabled land of Persia had established a national cult, Zoroastrianism, providing that diverse land a cultural unity that Roman emperors dreamed of. Roman Emperor Hadrian is alleged to have established a Roman version of this cult, called Mithraism. It was extremely popular within the army, and there were temples established in every city throughout the empire. They had an annual public festival for the birth of the Sun on December 25th that was extremely popular. This cult was widespread until Christians crushed it in the 4th century.

After the Nerva-Antonine dynasty fell, there was a year of repeated civil conflicts in an effort to take control of the Empire, each a regional uprising that would mirror future conflicts. This was followed by the less successful Severan dynasty. Severus himself ruled for nearly 18 years, but instead of naming a general as his son, he had his two underage boys named as Caesar. Predictably, this ended poorly, with a general rebellion that put the high priest of Elegabalus into the purple.

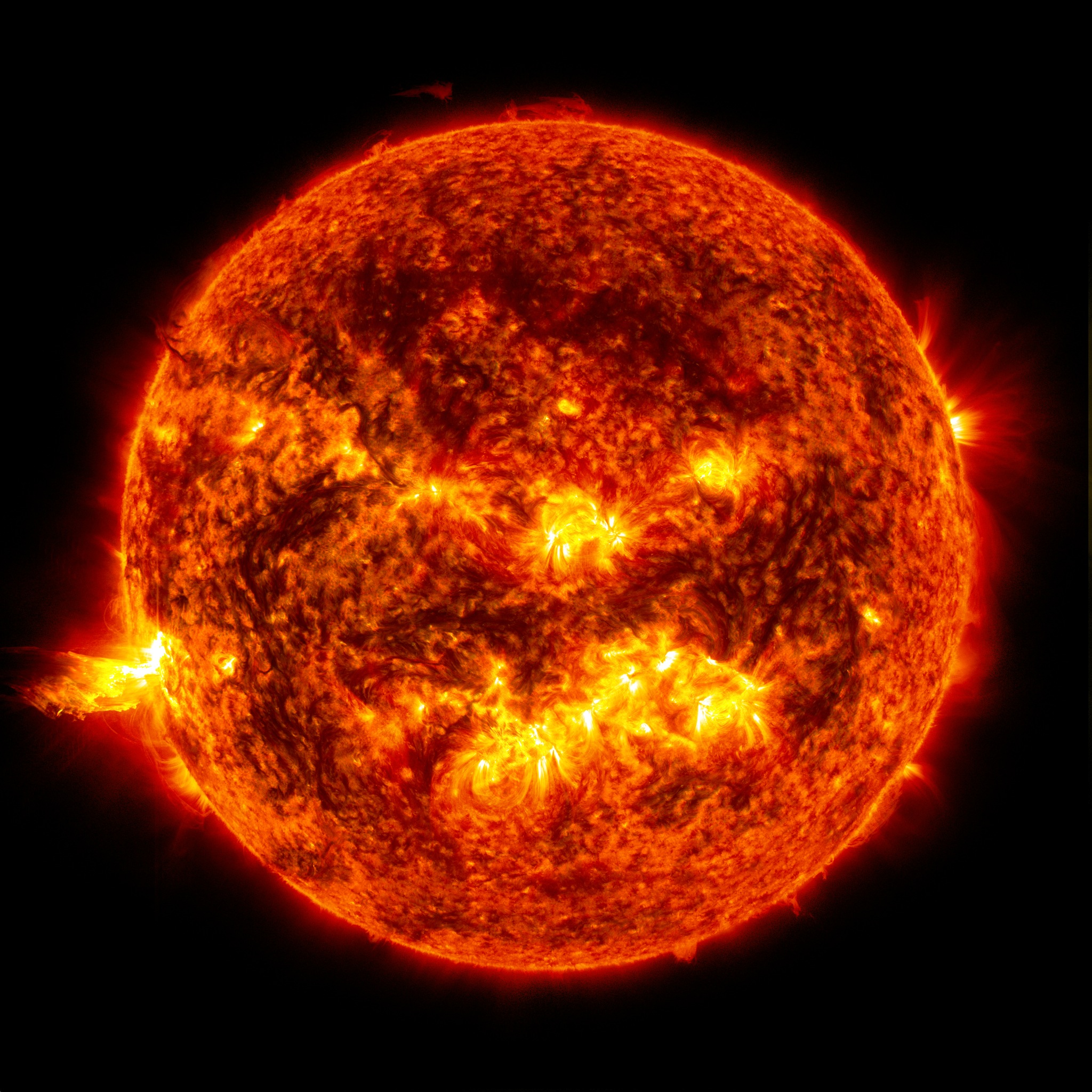

Due to the elevation of Elegabalus, the Imperial Cult theology structure was changed, knocking Jupiter out of leadership in favor of the Invincible Sun. Despite the grumblings from the Latin-speakers in the west, Imperial leadership had settled in the objectively wealthier and more cultured Greek-speaking east, and they had long before decided that they could do as they pleased and their rural, country-bumpkin cousins could go home sad about it. Many in the East worshiped the Sun as an apex deity, so having this be reflected in the Imperial Cult was an indicator of the collective power in the East.

By this point, those who had attended to Flavian temples probably looked to the years of prosperity and security under Flavian rule, compared it to what they were dealing with at the time, and decided that the Flavians were heroic emperors, worthy of worship, and that everything after that was the fall of Rome. They saw the promise of Christ’s return in the Gospels, and looked to the reincarnation of the Flavians to take control of Rome again. These temples likely fell away from the official Imperial Cult, which would have continued to add some of the later Caesars to the big list of honored Gods in Heaven, and joined together into a community or union in opposition to the official Imperial Cult, and thus stopped adding any additional Caesars for worship. The non-Pauline epistles were probably associated with the Flavian holy books around this time.

Following the rule of Elegabalus was his young cousin, Severus Alexander, who ruled for nearly 14 years before being strung up by his own troops. After this was fifty years of persistent civil war only occasionally peppered with emperors lasting longer than a year or dying of natural causes. Rarely would these claimants be around to see their coins minted, much less make contributions to the Imperial Cult. As the fiscal power of Rome dwindled, these civic wonders began to starve.

The Roman army was another wonder of the ancient world that suffered from Rome’s economic decline. Enormous in size and trained in techniques suitable to constrain crowds of farmers or legions of Persian troops, the Roman army enabled the expansion of empire, defense against invaders, and protection against internal rebellions. From the army came the generals, some of whom would become emperors, so much of the myth of Rome and about Rome centered on the military power of Rome, as the Flavians had emphasized. But the army was outrageously expensive, and the logistics of keeping legions stationed around the Mediterranean both fed and directed was a challenge that increased in size and complexity each decade.

The pressure of maintaining the army drove the gradual debasement of the silver dinar, the primary currency used for taxation. This created inflationary pressures that couldn’t be restrained by means legal or violent. Repeated civil wars destroyed resources needed for future support and development, further weakening the army and the economy. Coincidentally, steppe horse cultures were expanding into Europe, pressing Germanic tribes into Roman boundaries. As Rome’s ability to maintain military coverage diminished, it suffered from more frequent internal rebellions and was unable to prevent incursions across the continent.

More than once in this period, imperial claimants would attempt to gauge their relative popularity by having folks come out to the Imperial cult temples and give praise and incense to them as the current emperor, treating those who avoided this activity as political enemies. Flavian cult members, with their general disdain for anyone claiming to be emperor, might have found themselves persecuted for their preference to see a returning Titus or Trajan rather than any current emperor.

Around this time(?), the Pauline epistles were circulated, then appended to the collection of Flavian cult scripture. This represented a period of transition for the Flavian cult in terms of their relationship with the Son of God in their cult and the emperor de jure, and the conflict between the Flavian cult and the Imperial cult. An emphasis on the person of Jesus as a symbolic future Flavian ruler may have developed from this point as a means to speak of the preferred emperor without directly impugning the actual emperor. The cultists may have begun speaking of themselves as “Crestians” by this point, again to emphasize their preference for the best family of emperors. The Gospel of John was either created at this time(?) or along with Constantine’s additions(?).

(forward to Trinitarianism)

Leave a Reply